Schematic design is the stage that defines form, layout, and feasibility before details are locked in. Getting this stage right sets the tone for everything that follows in design and construction. Learn what schematic design involves, the common mistakes to avoid, and how to work effectively with your architect.

What is Schematic Design?

Schematic design is when the architect takes the owner’s program, budget, and site analysis and begins shaping them into preliminary drawings and layouts. The focus is on the overall design approach, showing form, scale, layout, and how spaces connect.

The goal of schematic design is to produce floor plans, site plans, and elevations that illustrate how the building fits the site and functions as a whole. This phase also checks basic feasibility against budget, schedule, building codes, and preliminary space needs for systems and sustainability strategies.

According to the AIA B101, schematic design ends when the owner approves documents showing the project’s scale, layout, and overall design approach. After that, the project moves into design development, where concepts become coordinated and buildable.

Quick Recap: What are the Design Phases?

The AIA (American Institute of Architects) outlines a standard sequence of design phases. Here’s how the process typically flows:

- Schematic Design (SD): Architects prepare early drawings to define form, scale, layout, and spatial relationships.

- Design Development (DD): Refines the approved schematic. Key systems are coordinated, materials are selected, and cost estimates are further updated.

- Construction Documents (CD): Full technical drawings and specifications are prepared. These documents are used for permits, bidding, pricing, and construction.

- Bidding or Negotiation: The architect helps the owner request contractor pricing, clarify documents, and review bids.

- Construction Administration (Construction Phase Services): The architect supports the build, answers site questions, reviews submittals, and helps verify that construction aligns with the design intent.

What About “Concept Design”?

While not an official AIA phase, many architects treat concept design as a separate creative step before or within schematic design. It focuses on big-picture ideas like form, flow, and massing.

In other countries, concept design may be a formal phase. For example, the RIBA framework (UK) lists it as Stage 2, coming after preparation and briefing. Always check what framework your team is using so you know what to expect.

Key Roles in the Schematic Design Phase

The key roles in schematic design include the architect, project owner, and client-side project manager, among others. Each plays a different part in shaping early design decisions. Here’s who’s typically involved:

- Architect: Leads the design process. Translates the brief into layouts, drawings, and concept options. Coordinates input from consultants and ensures compliance with planning, budget, and feasibility.

- Project Owner or Client: Defines priorities, goals, and non-negotiables. Reviews design options, provides feedback, and signs off on key decisions.

- Client-Side Project Manager: Manages day-to-day coordination. Bridges communication between the owner and architect, tracks design progress, and keeps decisions aligned with the brief.

- Engineers and Technical Consultants: Includes structural, MEP, and other specialists. They provide early input on systems, performance, and constructability.

- Quantity Surveyor or Cost Consultant: Checks costs against budget at each stage. Flags risks early and helps guide design decisions within financial limits.

- Other Stakeholders (as needed): Facility managers, compliance leads, or user reps may join to review layouts, access, or operational needs.

You don’t need the whole team at every meeting. But involve each role at the right moment so design decisions stay grounded in cost, scope, and real-world use.

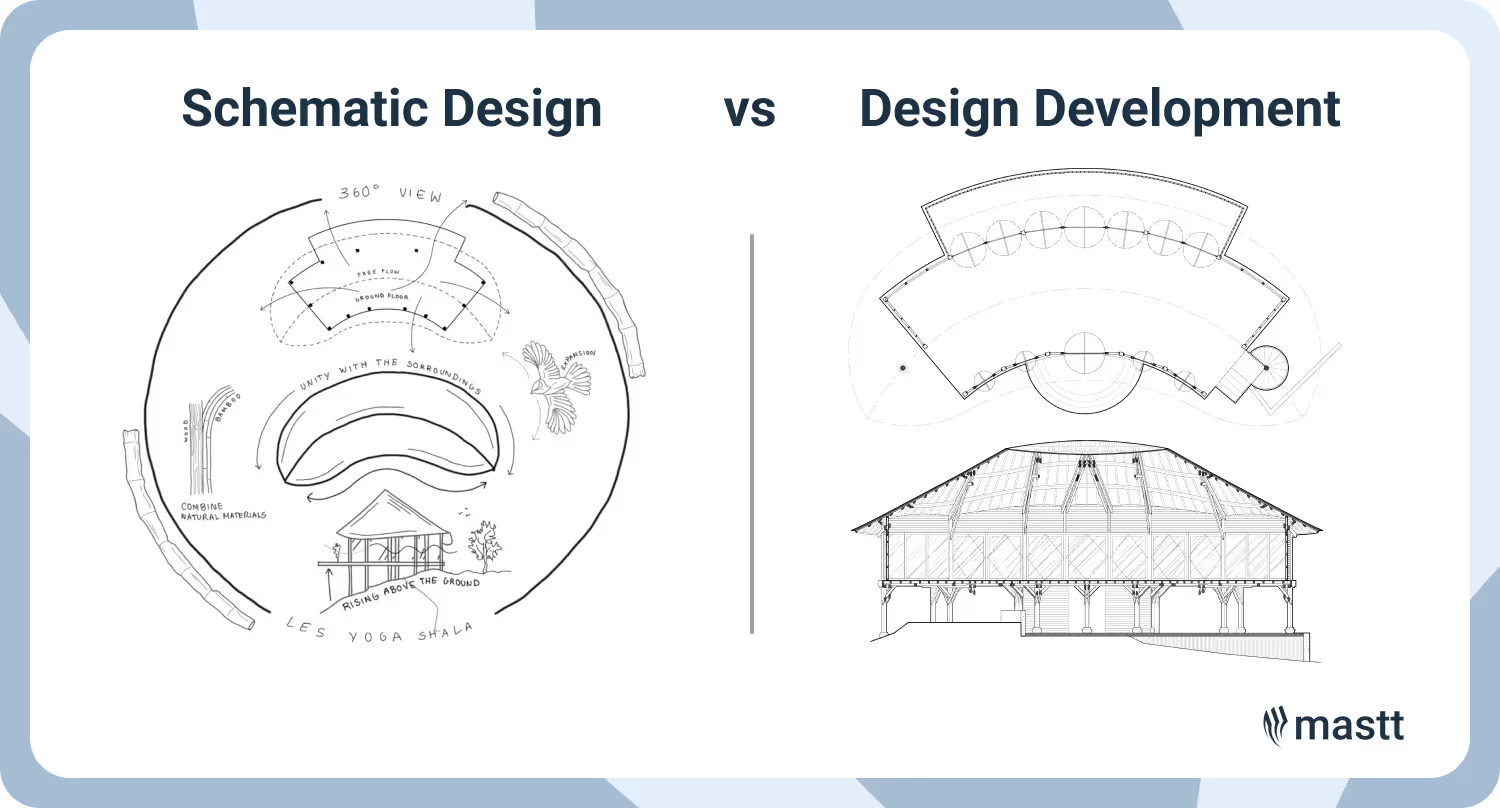

Schematic Design vs Design Development

Schematic design defines the big picture, while the design development phase fills in the details. The difference comes down to clarity, resolution, and decision-making around systems, materials, and constructability.

Each design phase plays a distinct role in moving the project from concept design to a buildable design solution. Here's how they compare:

Think of schematic design as setting the overall concept, and design development as refining it into commitment-level decisions. If schematic designs are preliminary sketches with potential, design development is where those design alternatives become technically sound and ready for construction drawing preparation.

What is Included in Schematic Design?

Schematic design documents include schematic drawings and written documents showing the project’s scale, layout, and basic building systems. Architects prepare visual plans, outline key technical choices, and note requirements guiding later phases of the architectural design process.

These deliverables give owners and the design team a shared reference before design development begins. Core items typically included are:

Architectural Drawings

These include floor plans, site plans, elevations, and schematic diagrams that show the project’s scale and spatial flow. They give a clear picture of how spaces connect and how the building fits the site.

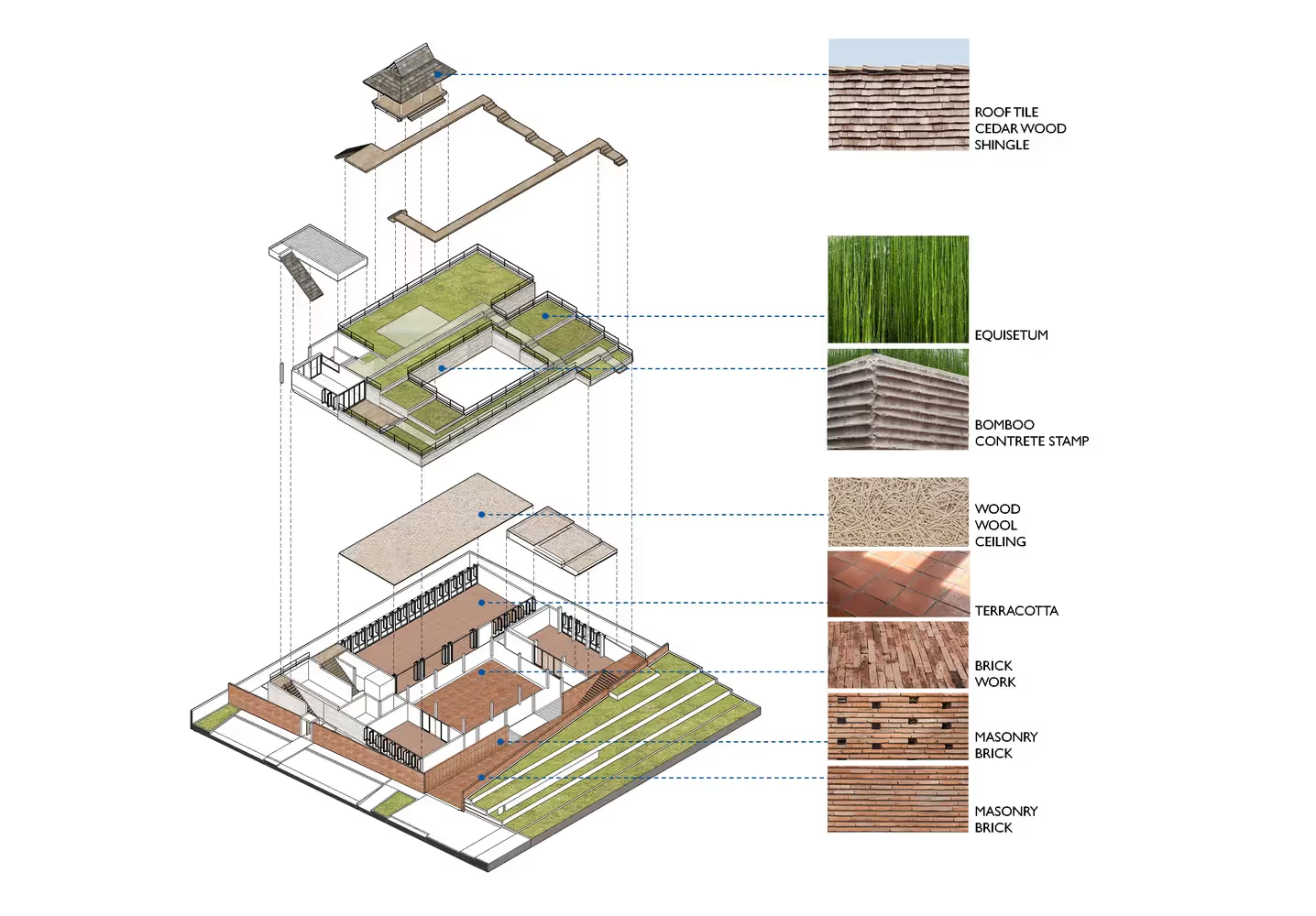

System and Material Notes

Architects provide early notes on structural systems, HVAC, plumbing, electrical, and possible material choices. These aren’t final specifications but serve as a guide for technical direction in later phases.

Visual Representation

Study models, digital models, or perspective sketches may be prepared to help visualize the design. These tools support communication with project owners and stakeholders.

These aren’t yet construction document-ready. The focus here is on preliminary design direction.

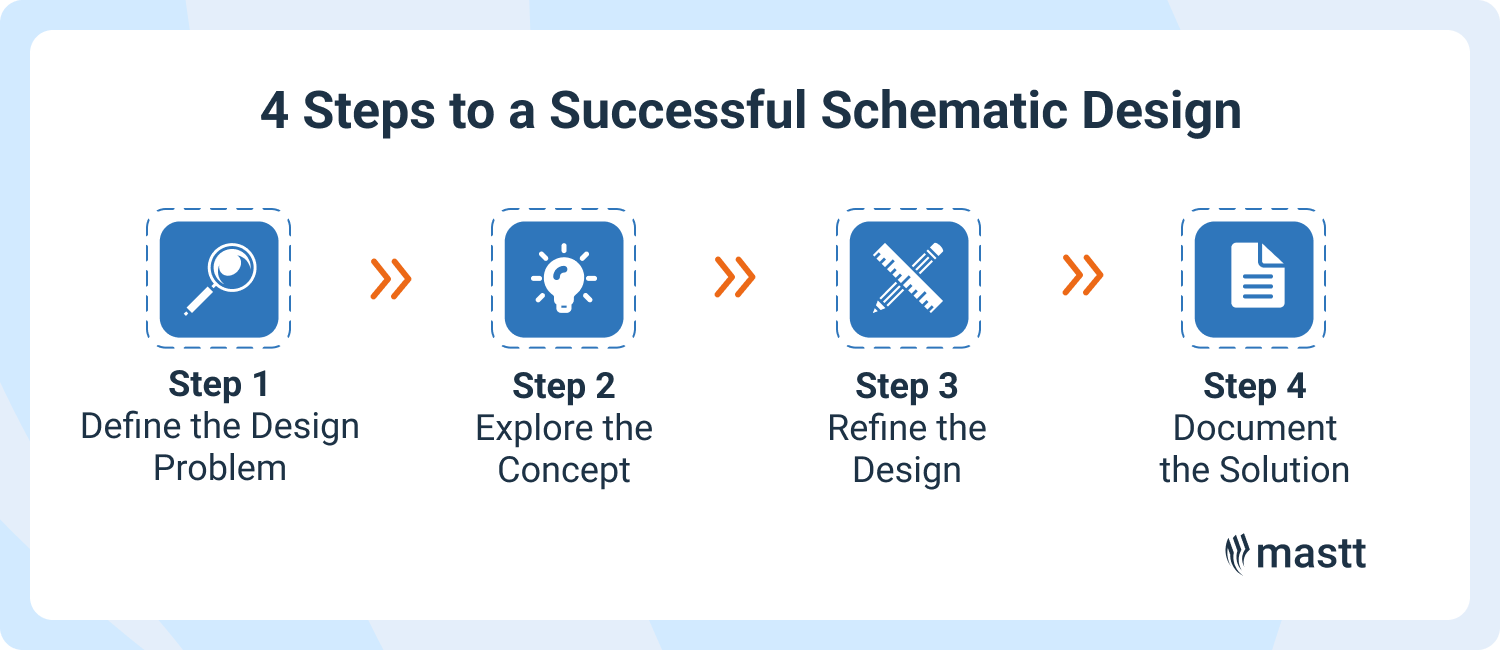

Step-by-Step Schematic Design Process

The schematic design process gives architects a structured way to turn early ideas into a workable plan. For client-side project managers and project owners, knowing how this phase works helps you stay engaged and make informed decisions.

In some workflows, especially outside the U.S., “concept design” is a formal phase that happens before schematic design. In others, concept work is built into the early stages of schematic design. The steps below reflect a common approach where both are explored together.

Step 1: Define the Design Problem

It starts with analysis. Your architect reviews the design brief, site conditions, constraints, and goals to define the project scope. At this stage, the focus is on understanding what needs to be solved.

💡 Tip: Leave space for unknowns. Priorities often shift once budgets, space limits, and planning rules come into focus.

Step 2: Explore the Concept

This is where early design thinking takes shape. The architect develops big-picture ideas about form, flow, and spatial relationships. These might be quick sketches, massing studies, or digital diagrams.

In some projects, this step overlaps with what’s called “concept design.” In others, concept design may already be done and signed off before schematic work begins. Either way, the goal here is to test ideas and compare design directions.

💡 Tip: Don’t expect a final answer yet. Instead, ask your architect to show a few good options.

Step 3: Refine the Design

Once a clear direction is chosen, your architect develops the layout further. They test the flow between spaces, adjust massing and circulation, and factor in feedback from stakeholders or technical consultants. Expect two or more iterations here.

💡 Tip: Revisit the project plan now to make sure the design still reflects your intent and goals.

Step 4: Document the Solution

The architect prepares schematic design documents. These include floor plans, site plans, elevations, and sometimes 3D visuals or diagrams.

These drawings aren’t ready for construction yet, but they’re detailed enough for approvals, stakeholder reviews, and early cost checks. Once approved, they become the foundation for design development.

💡 Tip: Review carefully. This is your lowest-cost chance to make changes before things start locking in.

Mistakes in Schematic Design (and How to Avoid Them)

The biggest mistakes in the schematic design phase come from unclear project goals, rushed approvals, and missing the right voices early in the architectural process. These often lead to rework, delays, or budget blowouts down the line.

These are the most common schematic design mistakes and how to prevent them:

1. ⚠️ Starting schematic design without clear priorities

When the project scope is vague, the design concept drifts. Architects will fill in the gaps with their own assumptions. That’s when stakeholders start pushing back, or the design professional flags a budget mismatch.

✅ Action: Lock in what matters like must-haves, nice-to-haves, and non-negotiables. Confirm alignment with execs and stakeholders and document it before the schematic phase kickoff.

2. ⚠️ Skipping cost reviews during early design

Preliminary sketches and schematic drawings may seem too rough for pricing, but every design decision affects structural integrity, building systems, and finishes. If no one tracks the project cost, you risk rework later.

✅ Action: Bring in your design team’s quantity surveyor early. Ask for schematic-level cost checks at each major round of preliminary design. Don’t wait for the design development phase.

3. ⚠️ Leaving out key stakeholders for too long

Don’t ignore facility teams, IT, operations, and compliance. They often catch issues that aren’t visible in the first round of architectural drawings.

✅ Action: Schedule at least one stakeholder review before schematic design documents sign-off. Focus on people who know systems, access, and compliance.

4. ⚠️ Prioritizing polished visuals before layout is solid

It’s tempting to fast-track visual representation to win buy-in or meet board deadlines. But if the layout isn’t nailed, you’ll waste time rebuilding later.

✅ Action: Hold off on glossy presentations until massing, adjacencies, and technical feasibility studies are confirmed. Build the right layout first, then enhance it.

Real-World Schematic Design Example: St. Petersburg Pier

The St. Pete Pier redesign shows how schematic design, when done right, can restore public trust and lead to lasting outcomes.

🛑 When a Design Misses the Mark: The Lens Proposal

In 2012, the city awarded Michael Maltzan Architecture the winning concept from a design competition. The bold scheme, known as “The Lens,” promised a futuristic waterfront experience.

But the public didn’t buy in. Residents said it lacked usable space and ignored local character. Protests and petitions followed. In the end, the city pulled the plug and went back to the drawing board.

✅ A Better Approach: Public-Focused Schematic Design

A second competition brought a new direction. The winning team, Rogers Partners, ASD, and Ken Smith Landscape Architect, proposed “Pier Park,” a scaled-down, people-first plan.

The schematic design reused parts of the old structure and added shade, splash zones, flexible lawns, and docks. It prioritized comfort, not spectacle. Landscape architect Ken Smith summed it up: “It’s where you can go if you have 50 cents or 50 dollars.”

This time, the City Council approved the schematic design. Public support was strong.

🚧 From Approval to Opening: Clear, Phased Delivery

With the schematic phase locked in, the rest moved forward with fewer bumps. Construction began in October 2016. The concept stayed intact through documentation, procurement, and delivery.

By July 6, 2020, the new St. Pete Pier opened. A civic space shaped by input, backed by design, and built to last.

👉 Why does this matter? The project avoided repeating past mistakes by aligning schematic design with public priorities, cost realities, and adaptive reuse. It’s a clear example of how early design thinking, when done right, leads to lasting results.

How to Work With an Architect During Schematic Design

To work effectively with your architect during the schematic design stage, stay focused on outcomes, give clear feedback, and ask how each design option impacts cost and performance. The best results come from early trust, decisive direction, and staying available for input.

Here’s how project owners and client-side PMs can keep the schematic design process moving:

- Set the decision framework early: Define who decides what, when design decisions are due, and what happens when scope or cost shifts. This avoids confusion and delays.

- Ask for design alternatives, not assumptions: When uncertain, ask your architect to explore a few viable options. Avoid locking in based on the first schematic drawing that feels “close enough.”

- Give timely, clear feedback: Respond quickly and be specific. Vague or late feedback leads to schematic designs drifting and cost overruns.

- Focus on project goals, not design solutions: Explain what success looks like. Let the architecture team work out the best way to achieve it through layout, circulation, and form.

- Collaborate, don’t micromanage: Communicate priorities, not instructions. Oversteering too soon often backfires and slows progress.

Architects move faster and deliver better building design outcomes when owners lead with clarity, not control. Give them something meaningful to respond to, and the architectural design will reflect both purpose and practicality.

🔁 Keep schematic feedback loops fast and traceable. Mastt’s collaborative platform lets owners and PMs attach files, log design decisions, and track cost impact.

Schematic Design is a Decision-Making Process

The schematic design phase isn’t just sketches on paper. It’s where critical design decisions take shape about money, time, and how the space will perform. For project owners, this is the moment to lead by defining what matters and driving toward clarity.

📌 Use Mastt’s real-time dashboards and automated reporting tools to track design progress, flag scope creep, and give executives clear, actionable insights.