A capital improvement project builds or upgrades public or private assets. Learn how these projects are funded, approved, and managed from start to finish.

Free Capital Project Management Plan Template! Streamline the planning, management, and delivery of large-scale projects while ensuring alignment, tracking progress, and mitigating risks effectively.

Capital improvement projects are large-scale construction or infrastructure efforts that improve, expand, or replace long-term assets. They’re planned out in advance, funded through a capital budget, and managed under a long-term strategy known as a Capital Improvement Plan (CIP).

Let’s talk about what capital improvement projects are, how they differ from other types of work, like repairs or maintenance, and why they matter.

A capital improvement project is a high-cost effort to build, upgrade, or extend the life of a long-term asset. These assets include roads, buildings, utility systems, and public facilities. The work often involves construction, major upgrades, or replacements, but not routine maintenance.

Capital improvement projects are funded through the capital budget and recorded in the Capital Improvement Plan. Each project typically has a multi-year scope, a defined cost, and a clear purpose, such as improving safety, expanding capacity, or meeting future demand.

To qualify, a project often needs to meet certain criteria: a minimum cost, a useful life of more than one year, and long-term value to the community or organization. Cities, school districts, and private developers rely on capital improvement projects to guide smart, strategic investments in infrastructure.

Capital improvement projects are different from maintenance and repair. Each project type serves a specific purpose and follows its own funding and planning process. It’s important to separate them clearly, especially when building out a CIP or capital budget.

Example: Repaving a worn-out city street would be a capital project because it improves the asset and extends its life. In contrast, patching potholes on that same road is considered maintenance, which is ongoing work to keep the asset functional.

Capital improvement projects shape the built environment on a large scale. For those in construction, they provide a steady pipeline of high-value, long-term work tied to infrastructure, civic buildings, utilities, and other essential assets.

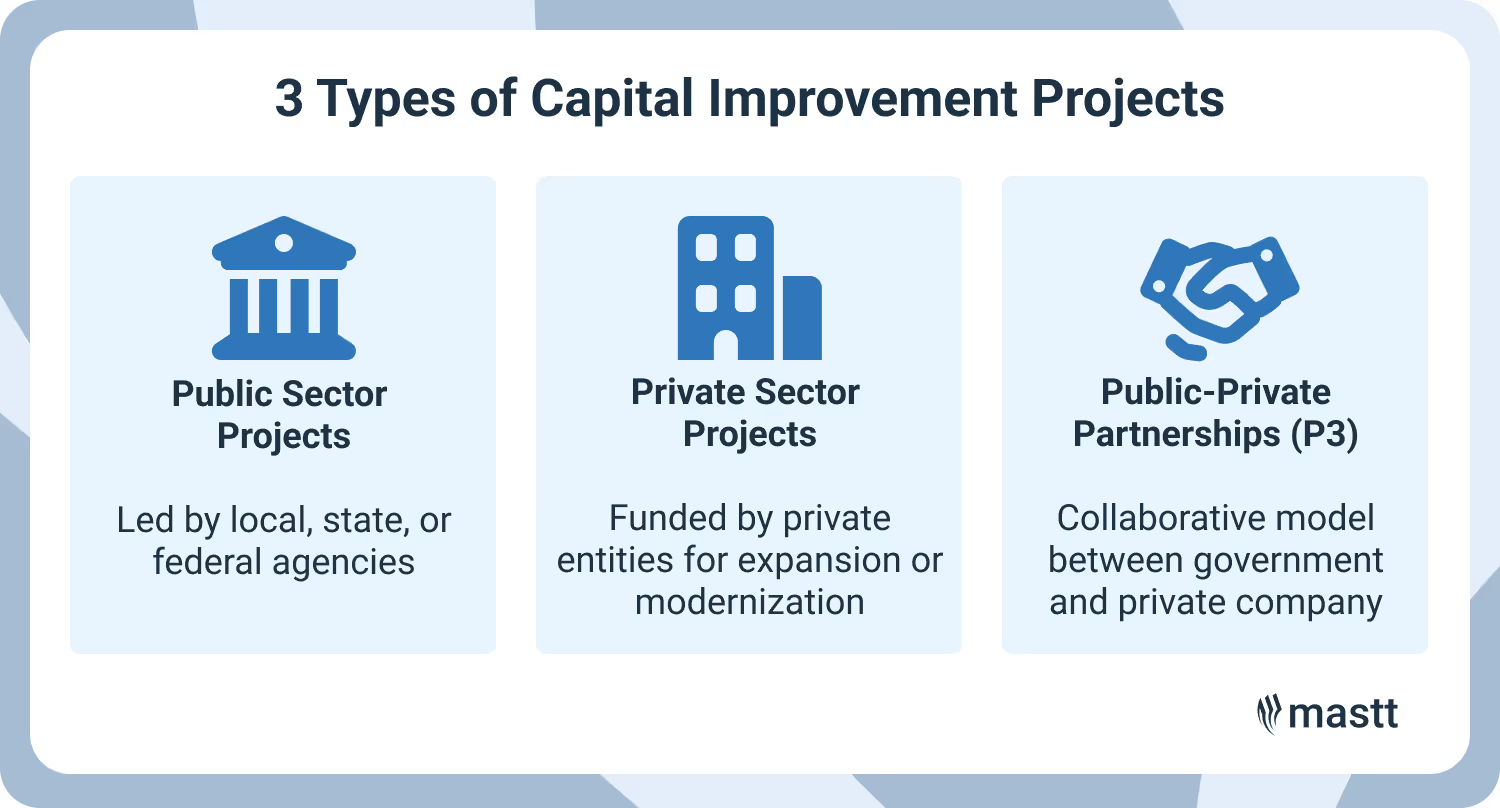

Capital improvement projects cover a wide range of work across public, private, and hybrid sectors. Each type serves different goals, but all involve major investment in long-term physical assets.

Public sector capital improvement projects are typically led by local, state, or federal agencies. These include:

These projects are often funded through a capital budget and tied to public service delivery. They require coordination with public works, planning, and finance departments.

Private entities also invest in capital improvement projects, especially when expanding or modernizing assets. Examples include:

While privately funded, these projects often follow the same planning and permitting steps as public projects and may still involve coordination with local authorities.

A Public-Private Partnership is a collaborative project delivery model between a government agency and a private company. Common structures include DBOT (Design-Build-Operate-Transfer) and concession agreements.

P3s let governments access private financing and expertise while transferring certain risks to the private partner. For owners and managers, this approach can shorten delivery time, improve lifecycle cost control, and reduce the need for upfront public funding. But it also requires clear contracts, performance benchmarks, and long-term oversight.

Capital improvement projects involve a wide range of professionals, each with a clear role in shaping scope, cost, quality, and outcomes. Coordination between stakeholders is critical to keep projects on track and aligned with strategic goals.

Project Owners and Owners’ Representatives

The project owner defines what success looks like. They set long-term goals, funding limits, and performance expectations. Owners’ representatives help translate those goals into project requirements and keep the team aligned throughout planning and execution.

Project Managers and Construction Managers

Project managers develop the project scope, manage changes, oversee procurement, and coordinate teams. They also track progress against milestones, cost targets, and timelines to keep work moving. Construction managers handle day-to-day delivery.

Design Professionals (Architects and Engineers)

Design teams balance form, function, and budget. They create construction drawings, model cost scenarios, and integrate sustainable practices. They also ensure the project meets building codes, zoning laws, and technical standards.

Financial Stakeholders and Funding Agencies

Funders include local governments, state programs, and federal sources like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Financial planners oversee bond issuance, grant compliance, and long-term debt service planning to keep financing stable.

Regulatory Authorities, Community Partners, and End Users

Agencies handle permitting, zoning, and code enforcement. Community stakeholders, like residents, business owners, local leaders, play a role too. Their input affects project acceptance, timelines, and the ability to operate without conflict or delay.

Capital improvement projects follows a multi-phase process designed to prioritize public needs, match them with available funding, and manage project delivery. Each step helps align needs, budgets, and timelines across departments and stakeholders.

The process starts by designating a lead department, typically finance or public works. This team coordinates all CIP activities. A CIP committee is then formed, often including leaders from departments with capital assets like transportation, fire, police, and utilities.

Key setup tasks include:

This step creates the structure needed to collect and evaluate proposals consistently across departments.

Departments submit project proposals based on known infrastructure gaps, risk reports, or community needs. In some cases, these ideas come from asset management plans or facility condition assessments. Where formal studies don’t exist, agencies rely on staff knowledge and operational history.

Each project proposal includes:

Proposals are ranked using a standardized rubric, regardless of whether funding is currently available. After the initial ranking, finance teams estimate available revenues and reassess priorities based on fiscal constraints.

Selected projects are compiled into a draft CIP document and multi-year capital budget. Visualization tools like GIS maps, Gantt charts, and cost breakdown structure help communicate complexity clearly to elected officials and the public.

This draft includes:

The draft CIP is then presented through public hearings, council meetings, or workshops. At this stage, public feedback and political considerations can lead to adjustments.

Once finalized, the first year of the CIP becomes the formal capital budget. There are three typical funding approval methods:

Long-term projects often include carryover provisions, allowing unspent funds to move into the next year’s budget.

Approved projects move into the preconstruction phase, which includes:

Procurement must meet public sector standards for transparency, fairness, and inclusion. Prequalification, DBE requirements, and cost control measures are typically part of this step.

Construction begins once contracts are awarded. Project managers use digital tools to oversee:

Scope changes follow formal CIP change control processes, which require written justification, cost-benefit review, and executive approval above a certain threshold. Delays or overruns are documented for performance reporting.

Contract closeout begins with final walkthroughs, inspections, and commissioning. Once complete, the asset is handed off to the operating department, which assumes responsibility for operations and maintenance.

The project team documents:

This information feeds into future CIP cycles, helping improve evaluation criteria, project scoping, and delivery methods. For agencies using performance dashboards or capital planning software, these insights are tracked and shared across departments.

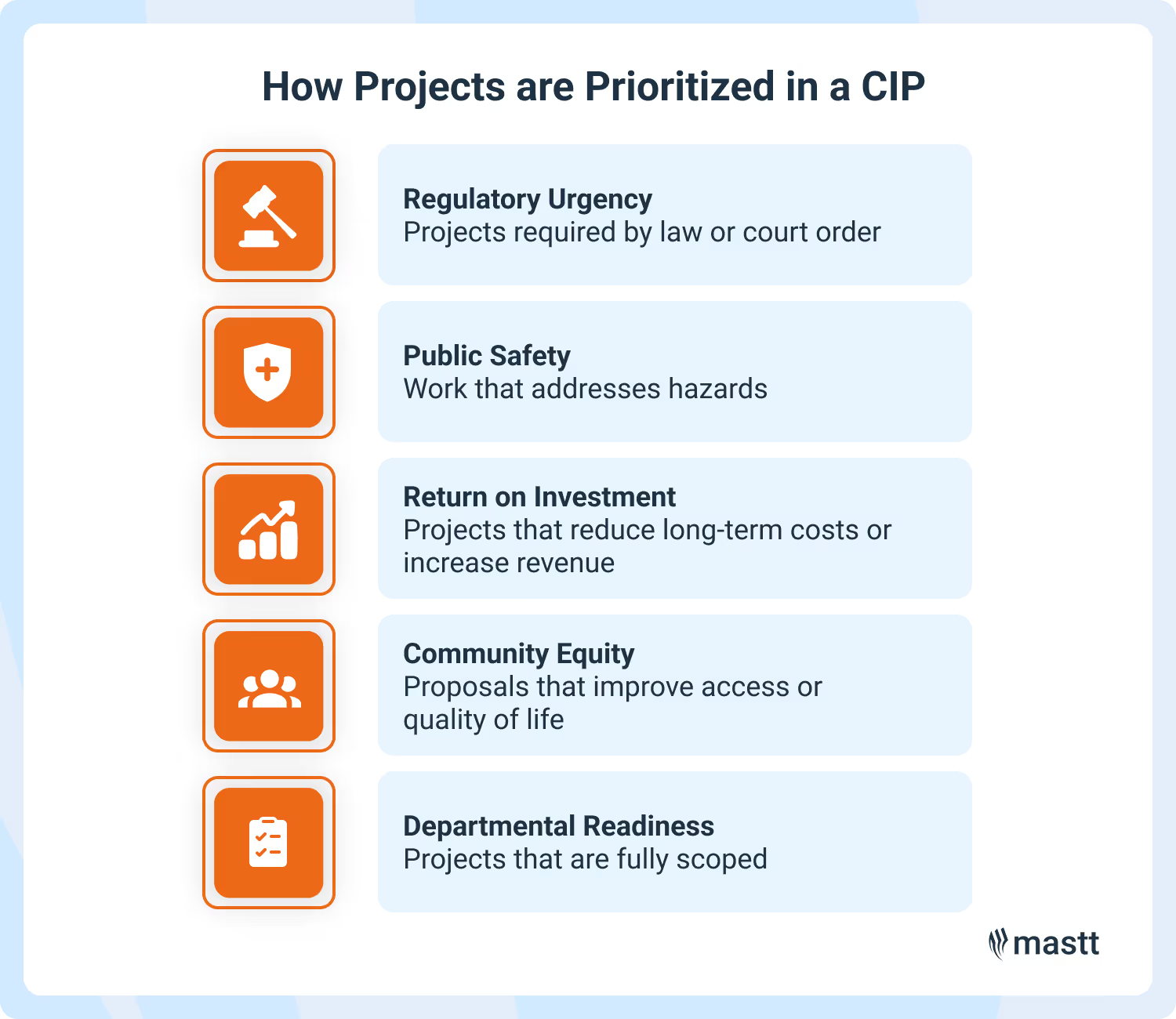

Capital improvement projects are prioritized using clear criteria that help decision-makers rank proposals based on impact, urgency, and readiness. This ensures limited funding goes to the projects that matter most.

Common evaluation criteria include:

Most agencies start with a scoring rubric to evaluate each project based on set criteria. The CIP committee or finance team reviews the scores and adjusts rankings as needed.

They also factor in stakeholder input from department heads, elected officials, and community members. Public feedback can shift priorities, especially for projects that affect safety, equity, or daily life in the community.

Capital improvement projects are funded through a mix of bonds, grants, cash reserves, and special financing tools. The right funding source depends on the project’s scope, timeline, and financial strategy.

Municipal Bonds

General Obligation (GO) bonds are backed by a government’s taxing authority and are often used for critical infrastructure, like roads or public buildings. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, are tied to the income generated by the project itself, like toll roads or utility systems.

Both require strong credit ratings and debt service planning to keep borrowing costs manageable.

Grants and State Revolving Funds

Many capital improvement projects rely on external funding from programs like EPA’s State Revolving Funds for water infrastructure or federal grants such as BUILD/TIGER. Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) are another source, especially for projects in low- to moderate-income areas.

These funds can reduce the need for debt, but come with eligibility rules and detailed reporting requirements.

Pay-As-You-Go (Paygo)

Paygo uses current revenues or cash reserves to fund projects directly. It’s common for smaller-scale improvements like equipment upgrades or minor facility renovations. While it avoids borrowing, it also limits how many projects can be funded in a single year.

Special Assessments and Dedicated Revenue

These funding sources are tied to specific areas or services. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) supports redevelopment by capturing new tax revenue from rising property values. Impact fees collected from developers help expand infrastructure in growing communities.

Other tools, like stormwater or utility fees, are earmarked for ongoing capital needs.

Capital improvement projects often face problems like shifting scope, labor shortages, and unpredictable funding. These issues can slow progress, increase costs, or derail delivery if not addressed early.

Here’s how to stay ahead of them:

⚠️ Scope Creep and Change Orders

Uncontrolled changes to project scope are one of the fastest ways to blow a budget or miss deadlines. These often come from unclear design documents, shifting priorities, or stakeholder pressure mid-project.

✅ Solution: Require formal change order requests, backed by cost–benefit analysis. Set approval thresholds that involve senior leadership for high-value changes. Track all scope shifts through a centralized system to avoid duplication or confusion.

⚠️ Labor and Material Shortages

Skilled labor can be hard to secure, especially during market peaks. Material costs and lead times also shift quickly, disrupting schedules and cash flow.

✅ Solution: Build strong partnerships with local trades and apprenticeship programs. Where possible, use modular or prefabricated elements to cut down on labor needs in the field and limit weather delays.

⚠️ Funding Uncertainty and Economic Volatility

Interest rate hikes, inflation, and shifting grant priorities can put approved budgets at risk, especially for multi-year projects.

✅ Solution: Use conservative revenue forecasts and build reserves into your capital plan. Add escalation factors to project estimates and break large projects into phases that can be adjusted based on funding availability. Identify backup funding options like grants or special assessments early in the process.

⚠️ Political and Community Opposition

Even well-scoped projects can face delays if residents or elected officials push back. Concerns may focus on cost, environmental impact, or equity.

✅ Solution: Engage stakeholders early, before design is locked in. Show how the project supports community goals like sustainability, accessibility, or economic development. Use tools like GIS maps or cost–benefit visuals to tell a clear, data-backed story.

Capital improvement projects often span multiple years, funding sources, and stakeholder groups. For project managers, success depends on staying organized, proactive, and clear at every stage.

Managing capital improvement projects with spreadsheets, PDFs, and outdated systems slows teams down and increases risk. Mastt brings structure, visibility, and real-time control to every stage of the CIP lifecycle.

With Mastt, project managers spend less time chasing data and more time delivering results. It’s built for the complexity and scale of capital improvement projects, without the admin overhead.

Capital improvement projects sit at the intersection of planning, policy, and execution. They’re strategic investments with long-term implications for infrastructure, budgets, and public trust.

Getting them right means aligning scope with funding, managing risk in real time, and keeping stakeholders informed every step of the way.

Cut the stress of showing up unprepared

Start for FreeTrusted by the bold, the brave, and the brilliant to deliver the future